Last week's huge and intense winter storm got a lot of attention due to the extremely high and in some cases record wind speeds measured, record low pressure, and widespread blizzard conditions. While that was big news at the time, the aftermath of this storm turned out to be more insidious and damaging than anything that occurred while the intense low pressure system was spinning over the U.S.

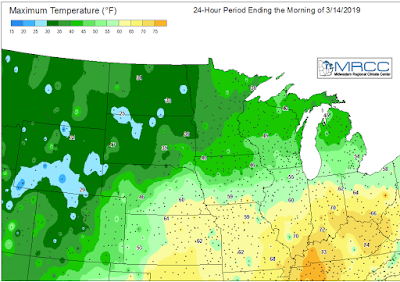

On the warm side of the storm, extending from Texas through the central Plains, warm most air was pulled northward by the strong circulation around the system. Temperatures in the 60s surged through Kansas and into southern Nebraska.

While the air was mild, there was still a lot of snow on the ground, and the soil underneath it was generally frozen.

| |

| Snow depth on March 11, 2019. Credit: NOAA NOHRSC |

|

| 4-inc soil temperatures under sod for the 24-hour period ending 3/13/2019. Credit: MRCC Regional Mesonet Program |

The mild air and heavy rain resulted in rapid snow melt. With the ground frozen, the water had no where to go except into rivers and streams. The snow across Nebraska held a water equivalent from one to more than two inches, so any runoff from the rain would have that much additional water from the melting snow.

|

| Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) on March 11, 2019. Credit: NOAA NOHRSC |

|

| These maps show the snow melt for the 24-hour periods ending the mornings of March 13 and March 14. Snow melt was 2 inches per day or more. |

By Friday, March 16 snow had disappeared from most of eastern Nebraska and western Iowa, draining into the rivers and streams.

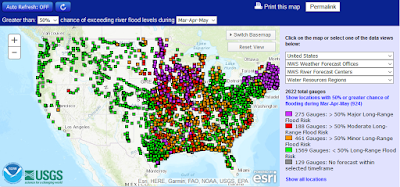

The sudden surge of water running off from the precipitation and melting snow along with ice on the rivers began to compound the disaster. Water flowed from smaller streams into rivers and many then into the Missouri River. While the Missouri River has been getting attention, a number of smaller rivers in Nebraska reached major flood stage.

The Missouri River went from normal to record flood stage at Nebraska City and Plattsmouth in just 48 hours.

|

| Hydrographs for the Missouri River at Omaha, Plattsmouth, and Nebraska City. |

|

| A comparison of eastern Nebraska in 2018 with no flooding (left) with 2019 (right). Credit: NASA Earth Observatory |

|

| Close-up view of the Omaha, NE area, 2018 and 2019. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory |

The National Weather Service will be updating its Spring 2019 flood outlook on March 21. You can be sure there will be a lot of people closely paying attention.