It was hard

not to follow the weather events in the southeastern U.S. this past weekend. While Hurricane Joaquin grabbed a lot of the attention, the well-forecast heavy rain in the Carolinas played second fiddle for the first day or two. Hurricane Joaquin, to be sure, was no slouch and hit the Bahama Islands hard. The devastation was focused on the southeastern Bahamas, particularly Crooked Island, Acklins Island, Long Island and San Salvador. Fortunately, the hurricane stayed well away from the U.S. mainland.

While Hurricane Joaquin did factor into the record-setting rain in South Carolina, the heavy rain would have occurred without the hurricane. I wrote about the

possible forecast issues with this system last week, the main concern being the stalled upper level trough in the eastern U.S. At that time it appeared that the bulk of the rain would be from North Carolina northward into New England. The trough did form a cutoff or closed low over the southeastern U.S. by Friday morning as forecast. There it sat through Saturday and Sunday, finally starting to ease out over the Atlantic Monday morning.

|

| 500 mb maps for 8:00 a.m. EDT Friday, October 2 (left) and Monday, October 5 (right). |

A surface low was located east of the upper air low, just off the coast. There was a strong onshore flow from the surface to the mid-levels of the atmosphere.

|

| Surface analysis for 8:00 a.m. EDT Saturday, October 6. |

This system tapped very moist, tropical air over the Atlantic and setting up an

atmospheric river of moisture feeding the storms over the Carolinas. The east coast system also tapped into the very warm moist outflow associated with Hurricane Joaquin. You can read some more about this interaction in

this article by Dr. Marshall Shepherd of the University of Georgia.

|

| Satellite water vapor loop showing moisture flow into South Carolina and Hurricane Joaquin. |

For a more technical summary of the meteorology behind the rain this weekend in the southeast, see

this article by the Capital Weather Gang at the Washington Post.

Rainfall amounts reported in eastern South Carolina - many of these from CoCoRaHS observers, were astounding, to say the least. Rainfall amounts over a four-day period exceeded two feet north of Charleston, SC, and near Columbia, SC. Here is a brief list of the highest rainfall amounts from CoCoRaHS observers in South Carolina and southeastern North Carolina.

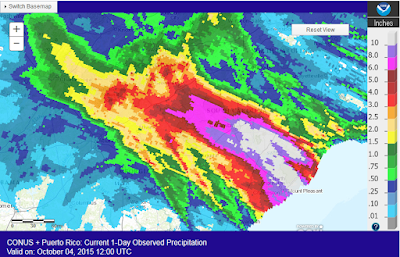

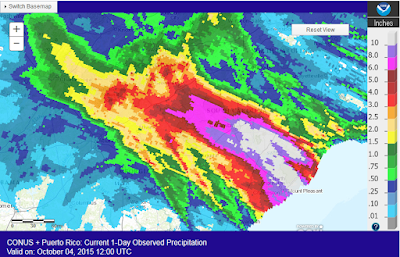

Below are the daily rainfall maps for the three primary days of the storm and the storm total map. It's clear that most of the state of South Carolina received more than six inches of rain from this system, with most of the coastal area of South Carolina and far southeast North Carolina picking up 12+ inches. The amount of 26.88 inches measured by the CoCoRaHS observer in Mt. Pleasant, NC over four days far exceeds the 1000-year, four day amount of 17.5 inches for Charleston. (Recurrence intervals are only published for 1000-year events or less, so the actual recurrence interval for this event was much higher). To further highlight the rarity of this rainfall, the amount of 26.88 inches is higher than the 1000-year, 30-day accumulation for Charleston. All of the superlatives used in describing this rainfall event ("historic", "unprecedented", "incredible") were right on the mark.

|

| 24-hr precipitation ending 8:00 a.m. EDT October 3. |

|

| 24-hr precipitation ending 8:00 a.m. EDT October 4. |

|

| 24-hr precipitation ending 8:00 a.m. EDT October 5. |

|

| Storm total rainfall from 8:00 a.m. EDT October 1 to 8:00 a.m. EDT October 5, 2015. |

What's a 1,000 Year Rain?

What do we mean when we say this was a "1,000 year rain"? This is called a recurrence interval, and is another way of saying that the probability of a rainfall amount equaling or exceeding a specified value has a probability of 1 in 1,000, or 0.1 percent in any year. It does not mean that the last time this amount was observed was 1,000 years ago, nor does it mean it will be another 1,000 years before it occurs again. It's just a statistical probability.

Here's a way to visualize this. Let's say we have a box filled with 1000 ping pong balls. One of those ping pong balls is red and all of the others are white. If you reach in to take a ball out of the box, there is a 0.1 percent (1 in 1,000) chance you will pick the red ball. Every time take a ball, you return it to the box. You reach in a second time and take another ball. The probability that you will select the red ball is still 0.1 percent, because you again start with 1,000 balls and only one is red. It is possible that you could select the red ball once, or twice in three draws, or never in 2,000 draws. However, the probability of the red ball in each draw is 0.1 percent. Similarly, a location could experience a 1000-year rain event this year, or again two years from now, or not for another 1,000+ years. The recurrence intervals are determined of analysis of the precipitation history for that area or location. For example, the 1,000-year rain for a 24 hour period in Charleston, SC is 14.80 inches, but for Phoenix, AZ the 1,000 year, 24-hour rainfall is 4.82 inches.

The sun was shining in South Carolina today, but the flooding continues on. More than a dozen dams have been breached, road damage is widespread and in many cases severe, and thousands of residents have lost their homes. As of this writing 14 people have lost their lives to the flooding. South Carolinians will be dealing with the aftermath for some time to come.

Finally, thanks to all of the CoCoRaHS observers in South Carolina and North Carolina who regularly reported rainfall during this event despite what were very challenging conditions. Your efforts are now part of the history of this storm.